For any foreigner living in Quebec, the surprise is annual. Quebec’s national holiday, June 24th, is a major event.

Canada day, the first of July, is largely ignored. How did this situation come about, unthinkable in any normally constituted nation (and I am choosing my words carefully)?

It’s because there is a fundamental flaw. The first of July 1867, date of Canada’s founding, was a holiday and the authorities organized several events. The high clergy was very favorable towards confederation, knowing itself masters of the powers delegated to the new province, notably education, the means of its self-perpetuation.

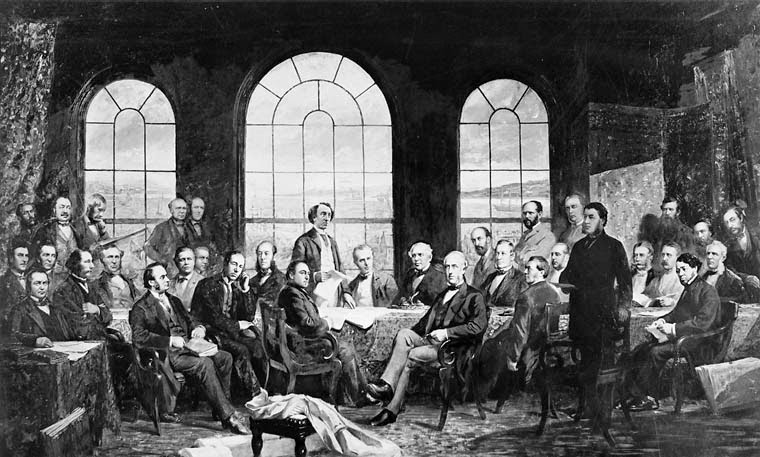

The Québécois, then called the Canayens – the others were Les Anglais – were particularly concerned. In the intense debate at the time, the project’s leaders, such as the conservative George-Étienne Cartier, even promised to hold a referendum on the subject. But having tested that method in New-Brunswick, and having been told no, they went back on their word.

Elections were held from August to September 1867, and served as unofficial referenda. The Red party (of whom the Quebec Liberal Party is a distant descendant) opposed confederation and preferred instead that Quebec remain an autonomous province within the British Empire, a sovereignty-association before its time.

That election was one of the most colorful in political history. First of all, as was normal at the time, the vote was not secret: the voters signed their name in a big open book. Only men 21 years and older possessing a minimal amount of wealth could vote, which reduced the electorate to a fraction of the adult population.

In addition, the clergy announced that voting for the Red party would be a “mortal sin” which would lead, for all eternity, to the flames of Hell. Mgr.Ouellet’s predecessors warned that the priests would even refuse absolution to the guilty, thus ensuring their damnation. (The historian Marcel Bellavance showed that in effect half as many absolutions were granted the following Easter than the previous one.) As a preventative measure, the curates also refused absolution, in the confessional, to the faithful who admitted having read opposition newspapers.

The result: 40% of the voters didn't show up, refusing to commit that sin and thereby reducing the electoral population. Other techniques were used:

Kidnapping: In order to be a candidate, you had to be present on the prescribed day and hour for a “nominal call” of the candidatures. Why not kidnap the opposing candidate – they would say retract – during the time of the procedure? This happened in three ridings, to the benefit of the conservatives.

The buy-off: Elsewhere, the conservative candidate, sometimes with the help of the parish priest, offered a sum of money or a nomination (nominations had to be approved by the clergy). In exchange, the liberal would withdraw his candidature during the nominal call, which would instantly elect the conservative. This happened in two ridings.

The disenfranchisement: The officers in charge of the nominal call, often conservatives, had the power to “disenfranchise” a parish, which is to say to annul an election, on various pretexts. The liberal part of the riding of L’Islet – half of the voters – was thus “disenfranchised”, as in three liberal parishes of Kamouraska, giving a narrow victory in both cases to the conservatives.

In that election, the most fraudulent in Quebec’s history and even by the standards of the day, 45% of the voters (thereby a majority of Francophones, since the Anglos voted conservative) nevertheless defied the bans and voted against the federation. Quebec’s membership to Canada was thus decided by less than 10% of the adult population, less than 20% of adult males. The Canayens of the time knew and historians today know that had it been a free vote, the electorate would have predominantly refused membership in Canada.

These facts are obviously lost to the collective memory. But they help to explain why the first of July 1867 never constituted for the Francophones of Quebec an occasion worth celebrating. That is why we never transmitted, from generation to generation, the urge to celebrate … a fraud.

And yet …

Certain people accuse the “separatists” of wanting to hinder Canada by making the first of July the legal date for the end of leases, instead of the first of May as was the case previously. In fact, the change was decided by the Liberal justice minister, Jérôme Choquette, great scourge of the separatists in 1971. The reason: so as to not perturb the school year of children affected by the relocations.

By Jean-François Lisée, June 30, 2010